Ancient Greece

There is no land without its story-tellers, and in the dawn of Hellenic civilization we find the half-legendary author of the Iliad and the Odyssey telling tales—some of them so long and elaborate as to be called epics, and some of them brief enough to be classed as short stories. Though the actual composition of the earliest Greek stories dates from a thousand or fifteen hundred years after the Egyptian tales, there is no doubt that they were sung or recited centuries before the great epics assumed the form in which they are now known.

The poet Hesiod, somewhat later than Homer, but before the opening of the Golden Age of Greek literature (Fifth Century, B.C.), inserted into his longer mythical and didactic works episodes which are, as a matter of fact, short stories, though they are inferior in workmanship to the ingenious tales with which Herodotus enlivens the pages of his fascinating History. Herodotus was much more of an artist than a mere recorder of facts. He was determined at all costs to make his work readable. Other and later historians strove to imitate him, and their books are full of anecdotes and episodes many of which might be extracted to demonstrate the gradual development of the form. Plutarch, in particular, was fond of relating incidents to illustrate the Lives of his heroes.

Though the fable probably originated in India, it was given a particular form in the so-called Beast Fable of the Greeks. This is a short story told in order to point a moral, in which respect it is not essentially different from most other stories, ancient and modern. It was in Greece that a collection of beast fables accumulated, and was attributed to a certain Tisop, of whom we have no authentic knowledge. That they are short and deal ostensibly with animals instead of human beings in no way prevents their inclusion in a collection of this sort. The best of them are masterpieces in the art of condensed narrative. Though the works attributed to Tlsop are now lost, they have been preserved in translated or adapted form by the Latin fabulist, Phaedrus.

It was after the close of the great epoch of Greek literature that the art of prose fiction arose in Greece. Antonius Diogenes, Xenophon of Ephesus, Achilles Tatius, Lucian, Parthenius, Longus and Hehodorus belong more especially among the writers of pure fiction. There were occasional exceptions, like Apollonius of Rhodes, who sought inspiration in the myths of the past, and developed the more or less crude incidents of the ancients into comely, if occasionally affected, stories. But the romance itself was originated by Xenophon of Ephesus, Lon- gus, and Heliodorus, and later developed by Achilles Tatius and Chariton. Still, the short story as an independent form was apparently not recognized. In The Robbers of Egypt, which is the first chapter of Heliodorus` Ethiopian Romance, we find a complete and unified short story. The Daphnis and Chloe of Longus is an early example of the “long-short” story.

Long before the final extinction of Greek romance the Greek forms had been carried over into the Roman world, where they were to flourish for a time, disappear, and then a thousand years later bloom again under the touch of the Italians.

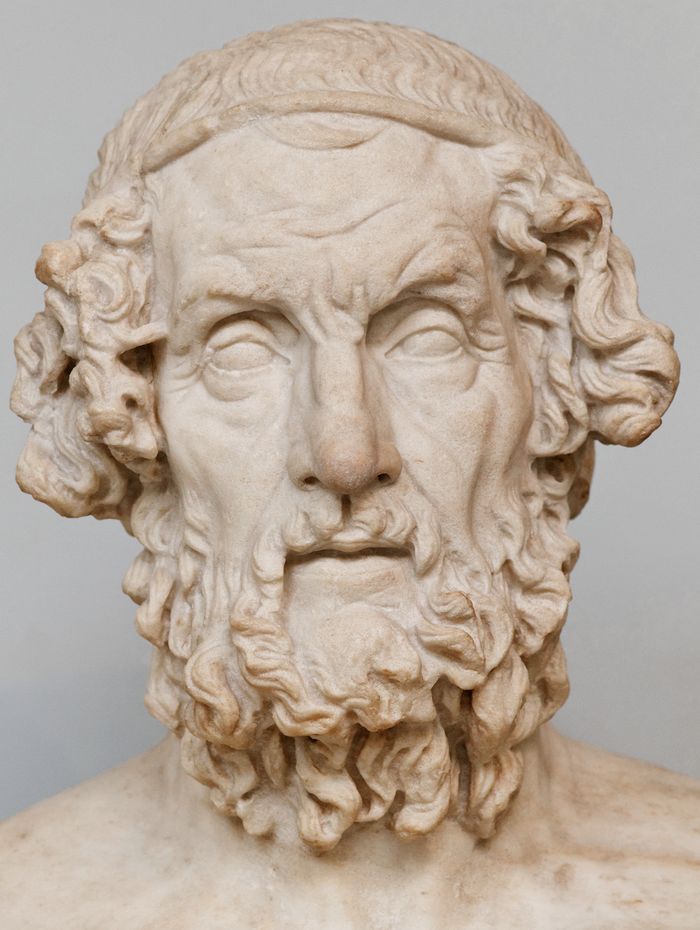

Homer (About 1000 B.C.)

The first mention of Homer dates from the Seventh Century B.C., but when he lived, or indeed whether he ever lived at all, are questions that have never been solved. The Iliad and The Odyssey were probably composed about a thousand years before the Christian era. The short story, as we know it, was not of course a recognized literary form, but Eumtsus ` Tale, in The Odyssey, happens to be an excellent example. It is told to Odysseus by the old swine-herd.

The present version, purposely reduced by the editors to more or less colloquial prose, is based upon three translations. There is no title in the original.

Eumieus` Tale

There is an island over beyond Ortygia—perchance thou hast -L heard tell of it—where the sun turns. It is a goodly island, though not very vast, with rich herds and flocks, and much grain and wine. There is no dearth, and no illness visits poor mortals. When men grow old there, Apollo of the Silverow, in company with Artemis, comes to them and kills them gendy with his shafts. On the island are two cities, which divide all the land between them. My father was king over all, Ctesius son of Ormenus, a godlike man.

“To this land came the Phoenicians, famous sailors greedy for mer-chandise, bringing many things in their dark ship. There was in my father`s palace a Phoenician woman, tall and lovely, and skilful in making beautiful things with her hands; her the Phoenicians deceived by their guile. As she was washing clothes near the hollow ship, one of them conquered her; love beguiles many women, even the noblest. The Phoenician asked her who she was and from what land, and she straight-way showed him the high palace of my father, and said, `I come from Sidon, rich in bronze, and am the daughter of the wealthy Arybas. The Taphians, who are pirates, seized me as I was coming from the fields, brought me to this land, and sold me for a great price to my present master.` Then he who had conquered her said in answer, `Wouldst thou return once more to thy home with us, to see again the high palace of thy father, and see thy mother? They are yet alive, and are reputed to be wealthy.`

“Then the woman made answer to him and said, `This may be, if you sailors will swear to bring me home safely.` Thus she answered, and the sailors swore as she bade them, and after they had sworn, the woman spake to them: `Say naught now; let none of you speak to me when you see me in the street, or even by the well, lest it be known and told to the old man here, and he suspect me and tie me fast and bring death to you all. But keep in mind the plan, and hasten to bring your freight for the homeward voyage. When your ship is full laden, send a messenger quickly to the palace for me, and I will bring gold, all I can lay hand upon. And there is more, besides, that I would bring with me: I am nursing a child for my master, a darling boy who runs about with me; I would bring him with me on the ship. He should bring a high price, if you sell him among men of other lands and other speech.`

“Then she departed to the fair halls. But the sailors remained among us a whole year, and gathered great wealth for their hollow ship, and when it was laden and ready to sail, a messenger was sent to tell the woman. A crafty man with a golden and amber chain came to the halls of my father. My mother and the maidens in the palace were looking upon the chain and holding it, offering the man a price for it, while he made signs in silence to the woman. Then he betook himself to the hollow ship. The woman then took me by the hand and led me out of the house. At the doorway she found the cups and tables of the guests who had feasted and waited upon my father: they had gone out to the meeting-place where councils were held.

And the woman concealed three cups in her bosom, and carried them away, while I followed her innocently. The sun sank and darkness came. Going quickly, we reached the harbor and the swift ship of the Phoenicians; the sailors went aboard, taking us with them, and sailed over the ocean, Zeus giving us favoring winds. We sailed continuously day and night for six days, but when Zeus, son of Cronos, brought the seventh, Artemis the huntress struck down the woman and she fell like a swallow to the bottom of the ship. The sailors threw her overboard, to the seals and the fishes, and I sorrowed. With the help of wind and wave they came to Ithaca, where Laertes bought me. It was thus that I first beheld this place.”

Read More about Diego Endara Tour